Sunday, May 14, 2006

Viktory

Viktory

The US Department of the Treasury's Office of Foreign Assets Control has at last added a whole wedge of Viktor Bout's companies to its asset blacklist. Not only that, but the key management including his brother Sergei, Richard Chichakli, Sergei Denissenko and Valery Naydo are on there too. It's not as comprehensive as I might have liked, but the core group is there: Air Cess, Air Bas, Centrafricain, San Air, Santa Cruz, Transavia, Irbis and Moldtransavia are in the list, as are the key holding companies CET Aviation and Southbound Ltd. There are also a few others I wasn't aware of (Air Zory, Business Air) and a couple I was suspicious but uncertain of (Gambia New Millenium).

As a bonus, a nine-pack of companies using Richard's address were zapped, as were a bunch of shellcos I'd never heard of in Gibraltar, Bulgaria and Delaware. Though imperfect, it's action, and would be worth a pint if I hadn't missed out through stumping the streets for Charles Kennedy. In the OFAC press release, there's a nice police-flick organisation chart I'll post here when I find a moment other than now.

Now, can I get away with putting a little Antonov 12 silhouette on the side of my computer for each company?

comments? | x

CW @ 1:30AM | 2005-04-27| permalink

You should paint a couple of Il-76s on the monitor for this list Alex.

Business Air is just another name for Air Bas. I knew about Air Zory but not New Millenium. "Rockman Ltd" in Bulgaria sounds interesting, but I'm sure its just one of the conduits for munitions from the Bulgarian state factories.

But most of the list is OBE - companies the network isn't using any more. The real value added is probably the Chichakli angle. As Rich is an American, I still don't understand what it means for him and his domestic companies to be on the list.

A perfect list would have had Click and ATI - shutting down the Baghdad contracts. (+ my personal choice "Alpha Omega Airways" :)

freighthauler @ 4:06PM | 2005-04-27| permalink

I wasn't aware that Air Zory was part of the outfit. In the early-mid 90s they used to do contract flights for Lufthansa Cargo.

A few more eurasian names would have indeed been nice on the Black List.

let's hope the treasury's office transfers the list to Dumsfeld's men.

Alex @ 10:32PM | 2005-04-27| permalink

FH, quite a lot of otherwise law-abiding people have dealt with the Bout system. It's one of the reasons it has survived: if you're implicated you won't betray. Also, if They work for LH and the UN and the USAF and tsunami relief, it's harder to believe they are bastards.

Crooks who have been at it a while in the end want to go legitimate. In London it was traditionally property development they went into.

No, I didn't know about Zory either.

Snarfel @ 4:23PM | 2005-04-29| permalink

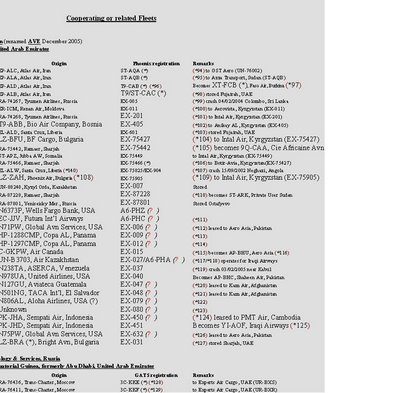

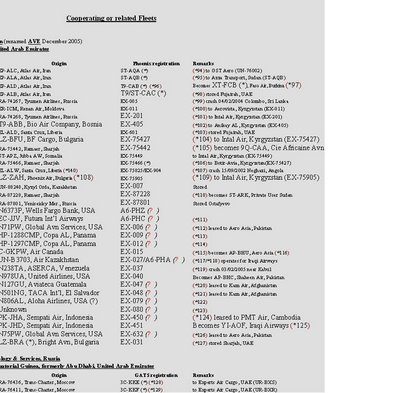

For an update of Bout's fleet, consult www.cleanostend.com

Snarfel @ 9:57AM | 2005-05-02| permalink

What shall we believe of this ?

"The U.S. Treasury Department announced that it had identified 30 companies and four people linked to Bout. Their assets will be frozen and it is now illegal for U.S. citizens to do business with them."

(http://allafrica.com/stories/200504280771.html)

This is quite in contradiction with the Los Angeles Times article "Blacklisted Russian Tied to Iraq Deals" (http://www.commondreams.org/cgi-bin/print.cgi?file=/headlines04/1214-04.htm)

Original: http://yorkshire-ranter.blogspot.com/2005/04/viktory.html

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Published on Tuesday, December 14, 2004 by the Los Angeles Times

Blacklisted Russian Tied to Iraq Deals

The Alleged Arms Broker is Behind Four Air Cargo Firms Used by U.S. Contractors, Officials Say

by Stephen Braun, Judy Pasternak and T. Christian Miller

WASHINGTON — Air cargo companies allegedly tied to reputed Russian arms trafficker Victor Bout have received millions of dollars in federal funds from U.S. contractors in Iraq, even though the Bush administration has worked for three years to rein in his enterprises.

Planes linked to Bout's shadowy network continued to fly into Iraq, according to government records and interviews with officials, despite the Treasury Department freezing his assets in July and placing him on a blacklist for allegedly violating international arms sanctions.

Largely under the auspices of the Pentagon, U.S. agencies including the Army Corps of Engineers and the Air Force, and the U.S.-led Coalition Provisional Authority, which governed Iraq until last summer, have allowed their private contractors to do business with the Bout network.

Four firms linked to the network by the CIA and international investigators have flown into Iraq nearly 200 times on U.S. business, government flight and fuel documents show. One such flight landed in Baghdad last week.

The list of the Bout network's suspected clients over the years includes the Taliban, which allegedly bought airplanes for a secret airlift of arms to Afghanistan. The Taliban is known to have shared weapons with Al Qaeda.

CIA officials expressed concern more than a year ago that air cargo firms linked to Bout were cashing in on U.S.-funded reconstruction efforts, but the warning did not reach the Coalition Provisional Authority until May. After conducting its own inquiry, the Coalition Provisional Authority allowed the companies to keep flying, insisting military officials who signed the contracts should deal with the problem. In other cases, officials said it was difficult to know if Bout was behind a particular air cargo firm because he continually changed company names and aircraft registrations.

Other federal officials said they had not known about the ban on dealing with Bout or about the Bush administration's effort to target Bout's network until relatively recently.

In a letter to Sen. Russell D. Feingold (D-Wis.) in June, Paul V. Kelly, an assistant secretary of State for legislative affairs, acknowledged that the department had "inadvertently" allowed contractors to deal with "air charter services believed to be connected with … Bout." Feingold, a member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, has taken a lead role in investigating Bout's activities.

"It befuddles the mind that the Pentagon would continue to work" with suspected Bout firms, said Lee Wolosky, a former White House official who tracked Bout for the Clinton and current Bush administrations.

Feingold said Monday, "What's obviously wrong is that U.S. taxpayer dollars are going to fatten the wallet of someone associated with the Taliban and with atrocities in places like Liberia and Sierra Leone."

An unreleased report prepared for the British Parliament, a copy of which was obtained by the Los Angeles Times, accused one cargo firm reputedly tied to Bout of flying weapons to war-wracked eastern Congo this year. The company is not involved in Iraq.

Reached by phone in Moscow, Bout responded angrily.

"You are not dealing with facts. You are dealing with allegations," he snapped before hanging up. His Moscow lawyer refused to answer questions.

During the chaotic period after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Bout was among the Russian entrepreneurs who seized opportunities to make a fortune. He built a global air cargo network by obtaining old Russian planes and using them to deliver, among other things, munitions to world trouble spots in defiance of U.N. arms embargoes.

A confidant of dictators, warlords and guerrilla leaders, Bout juggled a murky group of companies for much of the 1990s, transferring his planes' registrations from country to country. His fleet, which grew to nearly 60 aircraft by 2000, often carried legitimate wares such as flowers and fish. But U.N., American and British officials who tracked his activities say his empire's stock in trade was weapons, ammunition and helicopter gunships.

"He had his name on some companies but he has been removing himself from the scene, at least in name. He is finding more people to work for him that have no apparent connection to him," a U.S. official said.

Although Bout is wanted for money laundering by Interpol and Belgian authorities and various agencies raised red flags during the last year, his network continued to do business with some U.S. agencies and their contractors, officials said.

U.N. investigations and American officials have linked Air Bas, incorporated in Texas but based in the United Arab Emirates, and Irbis, a company registered in Kazakhstan, to Bout's aviation empire.

The same officials have also scrutinized two other airlines that flew into Iraq, British Gulf International and Jetline, for possible ties to Bout.

Among the firms holding U.S. government contracts that officials said were using the network's services: FedEx and KBR. The latter, formerly known as Kellogg Brown & Root, is a subsidiary of Halliburton, the Houston conglomerate formerly headed by Vice President Dick Cheney and holder of a massive no-bid contract for reconstruction projects in Iraq.

Under pressure to move quickly on the crisis in Iraq, officials have paid little attention to the welter of subcontractors and sub-subcontractors involved in the massive reconstruction effort.

"We have a saying in the Marine Corps: 'If you want it bad, you get it bad,' " said former Marine Lt. Gen. Jeffrey Oster, who was among the first to raise an alarm about the Bout-linked firms in May, when he worked as the Coalition Provisional Authority's deputy administrator and chief operating officer.

CIA officials expressed concern about possible dealings with Bout in October 2003 and the CPA investigated. The authority allowed the suspect companies to keep flying, saying that only military officials could terminate their contracts.

The Air Force did not act until September, when it pressed FedEx to stop using Air Bas.

Even then, some suspect companies continued to use flight facilities in Iraq under U.S. control, records show.

In the United Arab Emirates, for instance, a Sharjah International Airport official confirmed that on Oct. 28, an Irbis flight returned from Balad, the Iraqi central depot for military and reconstruction supplies. Military officials reported that an Irbis Ilyushin Il-18 freighter flew into Iraq in late November. Military and former CPA officials who oversaw flights in Baghdad say there appeared to be little oversight in the hiring and contract monitoring when it came to cargo firms that flew into Baghdad.

Concern over the Bout dealings has prompted several U.S. agencies to tighten regulations, officials said. Some Pentagon logistics officials say they have begun demanding more disclosure from contract firms using U.S. fuel facilities. And the State Department has warned its diplomatic posts to use caution in contracting decisions.

Air Bas officials denied any connection to Bout, but U.N. and U.S. officials said the firm had ties to the entrepreneur.

Victor Lebedev, Air Bas' general manager, was identified two years ago by U.S. officials as a Bout operative. He confirmed in an interview that his firm's planes had flown into Balad four times in October, carrying supplies for KBR, the Halliburton subsidiary.

Halliburton spokeswoman Wendy Hall said KBR had hired Falcon Express Cargo, a Dubai-based freight company. Falcon, in turn, subcontracted with Air Bas to haul the KBR cargo, Hall said. She said KBR is no longer using Falcon.

"KBR had no knowledge of a relationship between Falcon and Air Bas, and if we had known, we would have terminated the contract," she said.

FedEx spokeswoman Sandra Munoz said the company expected Falcon to "stick to the same standards we do," investigating subcontractors' safety records and operating authority. "We believe our procedures are still very solid procedures."

Defense Logistics Agency records show that Irbis planes bought fuel 142 times from military stocks in Baghdad — at a cost of $534,383. A FedEx official in the Emirates said Irbis was paid $22,000 for each of its round-trip flights.

Baghdad flight records obtained by The Times show that British Gulf also flew for KBR. Like the Air Bas executives, British Gulf officials denied any connection to Bout's network.

But intelligence agencies have linked Bout to some of the firm's planes. U.N. investigators examining bank records in the United Arab Emirates in 2001 found frequent money transfers between British Gulf and another Bout-linked air company, San Air General Trading.

"These were clearly suspicious money flows," said Johan Peleman, an Antwerp, Belgium-based investigator and weapons-trafficking expert who has worked for the U.N.

Igor Zhuravylov, British Gulf's flight manager, confirmed in an interview that his firm frequently flew supplies into Baghdad and other Iraqi locations. He said transport firms like his and Air Bas flew military materiel and other supplies into Baghdad with little supervision from U.S. contracting officials.

"We fly to Iraq and Afghanistan all the time, mostly for the U.S. government. But we never had a direct contract with them. We can't even approach them. All the contracts are made for us by other contractors."

A 2003 U.N. Security Council report on violations of the arms embargo in Somalia implicated both Air Bas and Irbis in Bout's aviation network.

Jetline also flew into Iraq twice for the British government, said Shavia Ejav, a spokeswoman for the British Department for International Development. Jetline has been identified by U.S. intelligence officials as tied to Bout. Company officials did not respond to requests for comment.

The propeller-driven Antonov and Ilyushin freighters flown by Irbis pilots "were coming in full speed all winter," said Air Force Reserve Maj. Christopher Walker, who worked from August 2003 until August 2004 as the CPA's supervisor of all aircraft flying into Iraq.

Walker and other officials who oversaw flight clearance at the Baghdad airport said they were not warned about Bout's suspected ties to the aviation companies until May, when an account in the French newspaper Le Monde revealed that British Gulf was flying to Iraq.

The CPA's Oster said he promptly ordered an investigation.

Bush administration officials said the Treasury Department had circulated a compilation of blacklisted individuals to military planners. But the list never reached the CPA, Walker said.

Bout's name, but not his firms or planes, was not added to it until July 22.

A U.S. official confirmed that now, "Air Bas is being considered for designation" by the Treasury's Office of Foreign Assets Control.

British Gulf's Zhuravylov recently recounted a story illustrating the agencies' lax procedures. In December 2003, he said, he struck up a conversation with a U.S. military fuel truck operator at the Balad airfield. Zhuravylov said the soldier gave him a blank government form, urging him to fill it out and mail it to military officials.

In April, "to my big surprise, I received a plastic card for each of our planes which allowed us to get military fuel," Zhuravylov said. British Gulf's business boomed.

"It was really so good," Zhuravylov said. "All by the mail. No inspectors, nothing like that. Write a letter, fill a form, get a card."

Original: http://www.commondreams.org/cgi-bin/print.cgi?file=/headlines04/1214-04.htm

_____________________________________________________________________________________

OSTEND AIRPORT/ARMS RUNNING

(Creation: 24/03/2001 – Last update: 14/04/2006)

Victor Bout’s air cargo companies

According to The Guardian, Victor Bout is thought to operate a cargo fleet of some 20 ex-Soviet aircraft through several associated cargo companies. This seems to be an underestimation, as evidenced hereafter.

A related story: arms dealer John Bredenkamp and the Belgian connection

An international arms merchant, mining entrepreneur and oil dealer, John Bredenkamp is thought to be Zimbabwe's main arms procurer and has provided arms, helicopters and pilots to Kabila's war-ravaged Democratic Republic of Congo (hereafter DRC).

Born in South Africa, Bredenkamp came to Zimbabwe as a child. In 1959 he joined Gallahers, a major player in the tobacco industry and transferred later to a Gallahers subsidiary, Niemeyers, in Groningen in the north of Holland. After 10 years with Niemeyers, in charge of the worldwide purchase of all existing varieties of tobacco, he left to start up his own business in 1976. This was the birth of Casalee in Antwerp, Belgium. The organisation grew rapidly and eventually had operations in most tobacco producing countries.

During the Ian Smith era Bredenkamp was in charge of the financial affairs of the Rhodesian Defence Forces and involved in sanctions busting for the Ian Smith regime in return for the highly lucrative concession to export all tobacco from Rhodesia through his company Casalee. Besides being a tobacco business, Casalee became a major international shipping and forwarding company. In the 1990s Casalee is alleged to have acted as an intermediary in the sale of anti-personnel mines to Iraq.

After selling Casalee in 1993 to Universal Leaf of the United States for US $ 100 million, Bredenkamp turned his attention to other areas of interest. Apart from tobacco he traded in fuel, cigarettes, foodstuffs, fish and other products in countries such as Russia, South-Africa, Zimbabwe, Mozambique and the Far East. However, having learnt to evade sanctions during the Rhodesia era of Ian Smith, Bredenkamp stayed in the arms-brokering trade with offices in Europe.

Meanwhile Bredenkamp had already switched sides after the birth of majority-ruled Zimbabwe in 1980, to become President Mugabe's strategic ally. In 1998 Mugabe and Bredenkamp became deeply involved in Kabila's war in the DRC against Uganda and Rwandan-backed rebels. In return for this, they claimed their share in the DRC's fabulous mineral wealth.

A third of Zimbabwe's army is fighting in the Congo. Bredenkamp's companies became the DRC's major suppliers of arms and Bredenkamp was directly involved in brokering substantial arms shipments from countries such as Bulgaria to Zimbabwe for probable use in Kabila's Congo.

To secure the military support of Zimbabwe the DRC government has been forced to grant valuable mining concessions and to install a Zimbabwean as head of the mining assets. Mugabe recommended the services of Bredenkamp, who consequently took over the management of Zimbabwe's concessions in the Congo.

Bredenkamp formed a joint venture project with Gecamines, the state-owned mining company in the DRC, to mine cobalt and copper in and around the southern Katanga province. Bredenkamp would control through his firm, called Tremalt Ltd and registered in the British Virgin Islands, a majority 80 percent stake in the joint venture firm, named Kababankola Mining Company. If unlike Billy Rautenbach, his predecessor at Gecamines, he succeeds in his latest venture, Bredenkamp intends to have a surplus in profits, sufficient to keep the Congo war machine oiled.

Not only Zimbabwe, Namibia as well is through one of Bredenkamp’s companies involved in fuelling the war in the DRC. After two years of denials, Namibia’s mining minister Jesaya Nyamu has admitted that the assassinated president of the DRC, Laurent Kabila, gave as a reward for military support, a diamond mine at Tshikapa, along the border with Angola. The Namibian company, belonging to the Namibian Defence Force and handling the Tshikapa mine, draws its directors from the country’s elite. One of them is the Belgian honorary consul to Namibia, Walter Hailwax. Hailwax is a director of Windhoeker Maschinenfabrik, producing military vehicles, and the local director of Bredenkamp’s arms brokerage company ACS International (PTY) Ltd.

As a wily merchant who has lined his pockets with dirty money, John Bredenkamp is a key player in the continuing mass-scale looting of the Congo and the persistent deprivation and molestation of its inhabitants.

Ostend Airport arms connection

At the end of May 2000 an attempt was made to fly four helicopters by Ilyushin freighter from Ostend to the Congo (ex-Zaïre but hereafter referred to as the Congo). President Laurent Kabila had ordered them for military purposes. Customs prevented the cargo from leaving Ostend for Kabila’s Congo. But permission was granted to transfer the helicopters to England and nobody was afterwards concerned about the helicopters’ final destination nor how they reached it. The embarrassing cargo disappeared and nobody seemingly felt guilty.

It becomes imperative to obtain a clear image of Ostend Airport as a pivot of the international arms trade.

Based on data of inside informers and that of the International Peace and Information Service (hereafter IPIS), this report will try to show, how often intricate networks involved in arms running to conflict-torn countries operate and, more specifically, the involvement of Ostend Airport. The war zones concerned are mostly Angola, Sierra Leone and the Region of the Great Lakes in Central Africa, all of them regions where mass-murders have occurred and where many survivors have been left permanently mutilated, for the sake of the diamond trade, monetary gain and power mania.

IPIS is an independent study and information service, covering international relations in general and in particular carrying out studies on arms trade, mercenary organisations and related subjects. It operates as an intermediary between, on the one hand, journalists and the research community and, on the other, peace, human rights and Third World movements. [1]

Our own data has been gathered from local informers and freelance investigators, who for their own safety, are not mentioned by name.

Certain companies are known to have organised arms traffic from their Ostend Airport branch offices. Such companies are extremely mobile and disappear as swiftly as they have been installed, possibly reappearing under another name to carry on with their evil activities.

Of the four following companies, which have been involved in arms running, one is still present in Ostend, while others were previously known under another name:

▪ Aero Zambia

▪ Avicon Aviation

▪ Westland Aviation and

▪ Air Charter Service.

The involvement in arms’ running of a fifth company, Johnsons Air, is described at the near end of this document.

1. According to IPIS, a company named Seagreen operated, until 1996, out of Belgium and was observed to be involved in arms trafficking. In November 1996, a Belgian daily, Het Belang van Limburg, revealed that two airlines based at Ostend Airport, Sky Air (see further on) and Seagreen, had been actively trafficking arms to Rwanda and to Goma in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). This had been going on throughout 1994 and 1995 during an UN-arms embargo on Rwanda. Empty planes of both companies took off in Ostend, to Burgas in Bulgaria, where boxes with AK47 riffles and ammunition of the company Kintex were loaded and flown to Central Africa. The owner of Seagreen, David Paul Tokoph and his brother Gary, both American citizens, were at that time living in Gistel, a little town near Ostend. Seagreen is no longer in existence, but David Tokoph afterwards acquired the bankrupt Zambian national airline. Subsequently this became a privately owned company, known as Aero Zambia, which also became involved in arms smuggling to the Unita rebel movement of Angola. [2]

The Times of Zambia reported that an aircraft operated by Seagreen, registered and licensed in Belgium, shuttled between Belgian airports and South Africa with arms cargo, that was off-loaded in Johannesburg onto a Boeing 707, registered as 5Y-BNJ (*1), for the final flight into Unita territory. Although it was bearing Aero Zambia colours, the latter aircraft was operated by one of Tokoph’s sister company, Greco Air, which had operating bases in Johannesburg and in El Paso, Texas, USA. El Paso is also the home of another Tokoph sister company, Aviation Consultants International, whose only services at that time included leasing aircraft to Aero Zambia. The Angolan government accused Zambian senior government officials of contributing actively to Aero Zambia’s arms smuggling towards Unita. Following the Angolan complains, Aero Zambia was then grounded by the Zambian Department of Civil Aviation for so-called flying without proper clearance to points outside Zambia.

A letter from the Angolan government to United Nations sanctions committee chairman Robert Fowler also reveals that David Tokoph constructed an airstrip at Mwansabombwe, an insignificant village on Zambia’s borders with Angola and the Democratic Republic of the Congo respectively. A Hercules C-130, registered as 9J-AFV, used to take off from this Tokoph-airstrip to unknown destinations. The end-user of the plane was Chani Fisheries, a Zambian company of the vice-chairman of Aero Zambia, Moses Katumbi, authorized to operate the plane temporarily in Zambia only. According to IPIS research, the man behind Chani Fisheries is a Congolese wealthy businessman, Raphael Soriano alias Katebe Katoto, who owns industrial fisheries in the lakes Tanganyika and Mweru, a copper and cobalt trading company and a luxurious domain in Bruges, Belgium, named ‘Ter Heyde’ as well, and besides who in October 2001 announced that he would run for president during the transition period of the DRC. However, the C-130, manufactured in the USA and considered as an unclassified defence article, was grounded in Angola in September 1997, when it appeared that Katebe Katoto Soriano had tried to sell the aircraft to a Portugal-based trading company, in contravention of sales conditions imposed by the American Office of Defence Trade Controls. Further investigation revealed that just before the illicit sales agreement between Chani and the Portugal-based company was concluded, the Hercules C-130 had apparently been used for the delivery of military equipment to the rebel troops of Laurent Kabila approaching Kinshasa, the capital of Mobutu’s Zaire then.

Aero Zambia’s owner, Tokoph, is reportedly a former associate of right-wing American politician Oliver North, who played a key role in the Iran-Contra scandal and was Washington’s point man in the days when the United States covertly sponsored Unita. In the early 1980s, Oliver North was, according to the Belgian newspaper De Morgen of 2 October 1995, also a regular visitor to Ostend Airport. During the Iran-Iraq war, David Tokoph has been connected to the Iran-Contra affair through his Texas company, Aviation Consultants International, and his Mexico-registered company, Greco Air, who both leased aircraft to a company, called Santa Lucia Airways.

In May 1987, a Belgian parliamentary commission of enquiry confirmed, that Santa Lucia Airways was indeed operating in Belgium as a subcontractor to the Belgian national airline Sabena and was connected to illegal weapons flights to Iran and to Unita in Angola as well, via the military base of Kamina in the Congo. [3] Santa Lucia had until May 1987 an office at Ostend Airport, where its aircraft was also periodically stored for maintenance purposes. Details, for instance, were known of a Santa Lucia Boeing 707, registered as J6-SLF (*2), linked to an illicit shipment of weapons to Israel for transhipment to Iran. This aircraft, re-registered as EL-JNS, has later been operated by Sky Air and flew in 1996 a number of boxes of Kalashnikovs from Bulgaria to Rwanda (see further on).

Another question remains as to what a mystery Aero Zambia aircraft was doing in Asmara, Eritrea, where it lies stripped of its engines and wings. At the beginning of the Ethiopia-Eritrea war in 1998, the Boeing 727, registered as 5Y-BMW, was hit by an Ethiopian air missile, as it stood parked at Asmara airport. Based on the allegations of Aero Zambia’s involvement in arms trafficking towards Unita, the presence of the aircraft in Asmara, being targeted by the Ethiopian missiles, has become more ominous, but its mission has never been revealed.

In May 1996, the Board of Directors of Aero Zambia decided to open a branch office at the Ostend Airport, but moved its office in August 2003 from the airport to the Ostend Jet Center, where the Russian arms dealer Victor Bout started in 1995 his murky business (see further on). Officially the activities of the Ostend branch had to remain confined to the representation of the company under Zambian law in Belgium and Europe. It was the Ostend branch that, at the end of May 2000, had been ordered by the Brussels firm Demavia to arrange the above-mentioned transfer by plane of the four helicopters destined for Laurent Kabila.

David Tokoph, a fervent supporter of George Bush Jr and the proud owner and simultaneously operator of a F-100 Super Sabre fighter, based in El Paso, is still very active in the air business, since in August 1997 he took over the Johannesburg-based company, Interair South Africa, with his brother Gary installed as vice president of the company.

2. A British airline, named Sky Air Cargo, used Ostend Airport in 1996 as the home base for its then 33 year-old Boeing 707, Liberian-registered as EL-JNS (*3). In October 1996, the plane flew a number of boxes containing Kalashnikovs from Bulgaria to Rwanda. [4] In 1997 it made at least 25 flights from Ostend. The plane was also seen several times from 1996 to 1998 on the military apron of Otopeni airport, near Bucharest, Romania. Under suspicion of illicit actions, the aircraft then adopted the airport of Sharjah (United Arab Emirates) as its new home. In 1998 Sky Air was, together with Air Atlantic Cargo, responsible for airlifting some 2,000 Kalashnikovs, 180 rocket-launchers, 50 machine-guns and ammunition from Bulgaria to the UN-embargoed Sierra Leone, by order of the London-based private military corporation (PMC), Sandline International. [5] The Pakistani owner of Sky Air, Sayed Naqvi, admitted that his company delivered the weapons, and on May 10, The Observer reported that it had obtained documents that confirm details about a Sky Air arms flight. The Sky Air Boeing 707 was loaded with weapons at Burgas airport on February 21, 1998. The aircraft then departed for Kano, Nigeria, where it made a stopover before delivering its cargo to Sierra Leone.

In January 1999, the London Sunday Times also reported that Sky Air Cargo of London and the Ostend-based Occidental Airlines, owned by a Belgian arms dealer, Ronald Rossignol and a British pilot, Brian Martin (see further on), were using ageing Boeing planes that were loaded with AK47 rifles and 60mm portable mortars at Bratislava, the Slovak capital. Supposedly destined for Uganda, the arms, 40 tons at a time, went to Liberia and the Gambia, where they were put on flights for a bush airstrip at Kenema in Sierra Leone, occasionally through the services of Victor Bout (see further on). Eventually the arms were flown to rebels in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). [6]

In a taped video interview, a British pilot described how in 1999 and 2000 he flew AK47 rifles from Rwanda and Uganda into the rebel-held town of Kisangani in the DRC. He claimed the planes were registered in Swaziland for Planet Air, which was named by the US government as supplying arms to eastern DRC. According to Amnesty International (AI), Planet Air has offices in West London run by the same person who managed Sky Air Cargo, the company that had operated the Liberian-registered cargo plane EL-JNS (now 3D-ALJ: *4) and, says AI, strangely enough, the Liberian Civil Aviation Regulatory Authority was run by a UK business in Kent, England, during 1999 and 2000. When too many questions were asked, the Kent businessman switched to selling registrations for Equatorial Guinea. UN investigations have shown that aircraft on these UK-run registers were used for international arms trafficking to Angola, Sierra Leone and Central Africa, including the DRC. [7]

The Pakistani owner of Sky Air, since 2001 in liquidation, seems to have strong connections with a new Ostend-based company, Avicon Aviation, founded in May 1998 by a Pakistani resident in Karachi. The man in charge of the Ostend company is another Pakistani living in Ostend and during the mid 1990s Ostend station manager for Sky Air. According to certain sources, ‘Avicon’ stands for Aviation Consultants, the Texas company of David Paul Tokoph. This would confirm close connections between Paul Tokoph and Sayed Naqvi, which already existed at the time when, as recounted earlier, their respective airlines Seagreen and Sky Air were actively trafficking arms to Rwanda throughout 1994 and 1995.

The above-mentioned Air Atlantic Cargo, owned by Nigerians, had Ostend and Lagos as operating bases. Its fleet was restricted to two Nigerian-registered Boeing 707s, 5N-EEO (*5) and 5N-TNO (*6), which in 1997 made a combined total of 126 flights from Ostend Airport. In January 1999, the English newspaper The Observer confirmed Air Atlantic Cargo’s involvement in illicit arms traffic and quoted that it was being linked to suspected arms shipments to Unita rebels in Angola and a possible breach of United Nations sanctions. The allegations relate to a Boeing 707 spotted on three separate occasions at Pointe Noire in western Congo, just north of enclave Cabinda, in September and October 1997. Its objective appeared to be to drop off military equipment and escape the war zone unnoticed. However, monitors from Human Rights Watch noted the Boeing’s markings and saw Unita troops unload ‘military-looking’ crates. HRW suspected that the crates contained arms destined for the civil war in neighbouring Angola. It was the first in a series of sightings of aircraft marked ‘Air Atlantic Cargo’.

Air Atlantic Cargo was a British company with offices in Kent. The planes spotted in Central Africa were those registered to the Lagos-based Air Atlantic Nigeria, the major shareholder in the British company. Air Atlantic Nigeria was run by a Nigerian businessman, Adebiyi Olafisoye, the senior executive of AAC in Britain, living in north London, and it closed down in 1999.

Ten months after the Pointe Noire sighting, a cargo plane was seen making drops to troops on both sides of the civil war in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Interviews with former crew members revealed that on 4 August 1998 one of Air Atlantic’s Boeings landed at Goma in the east of the country with 38 tonnes of arms from Burgas in Bulgaria. A week later the other aircraft was spotted in Namibia, delivering 21 tonnes of arms to President Laurent Kabila’s troops. Crew members later confirmed to aid agency researchers that this was the plane that had supplied troops fighting the DRC government. The plane then flew to Botswana and unloaded armoured cars destined for Kabila’s troops in Kinshasa. They were almost certainly part of a consignment of 36 reconditioned vehicles manufactured by the British company Alvis of Coventry for the Belgian Army and sold to Botswana between 1995 and 1997. [8]

Ron Brennan, a director of Air Atlantic Cargo, told that he did not ‘have a clue’ what cargo the Boeing 707s have been carrying in Africa, but he fiercely rejected suggestions the company had been involved in arms trafficking. When pressed, Brennan conceded that one of the planes had been chartered by a Congolese airline. ‘What they use the planes for, is anybody’s guess,’ he said.

3. Liberia World Airlines has its main office in Gibraltar. In 1988 a Belgian company NV Liberia World Airlines Belgium was constituted, which went bankrupt in 1994. The company was co-owned by a Liberian citizen and a native of Kinshasa, Duane Andrew Egli. The latter took residence in a hamlet on the Franco-Belgian border. A few weeks after the bankruptcy, the Brussels-based company Westland Aviation, also owned by Mr Egli, was transferred to the Ostend Airport. The company obtained a very substantial injection of new money, fifty per cent of which was contributed by a Swiss company, Avtec AG, Basel. Before he left the former Zaïre in 1988, Duane Egli owned an airline company, based in Kinshasa and called Lukim Air Services.

Westland Aviation was active in Ostend until January 2004. It had two DC8 aircraft based on that airport. One of them had its last authorised flight in Europe in January 2001 and it took the opportunity to fly to Uganda. The other Liberian-registered aircraft EL-AJO (*7) was operational until December 2001, when it took off for Sharjah (UAE) to be sold to Cargo Plus Aviation. In 1995 it was accused by Human Rights Watch of illegal arms transport. The Belgian authorities assured HRW that an investigation was already in progress as a result of their own information. In spite of the investigation, the same aircraft was, in August 1996, again convicted of illicit transport. The aircraft was impounded by local authorities in Goma, the Congo, after it was found to be carrying military clothing destined for Uganda and hidden under a load of relief supplies. [9]

Nevertheless until at least 2000 a great number of humanitarian flights were assigned to the same airplane EL-AJO. This means that Belgian authorities are not interested in the reports of HRW or of similar pressure groups and consequently have omitted taking preventive action. As a result, certain companies manage to make a profit from acts of war, by mixing relief supplies with military equipment.

A company closely connected with Westland Aviation, Airline Management Group, ran a hangar where, besides LWA-aircraft, other old airplanes received maintenance or were refurbished. Whether AMG owned a maintenance licence, is not clear. However, the company went bankrupt in July 2003. Six months later, in January 2004 Westland Aviation went bankrupt as well.

Meanwhile, Liberia World Airlines Gibraltar reappeared as Ducor World Airlines and acquired in May 2001, with the contribution of Avtec AG, a Lockheed TriStar from LTU Airways, Bulgarian-re-registered as LZ-TPC. The aircraft, stored at Ostend Airport, was converted to a freighter. At the end of 2001 DWA intended to acquire an additional four aircraft to replace its fleet of two DC8 aircraft, EL-AJO (now 3D/3C-FNK: *8) and EL-AJQ (now 3C-QRG: *9). It was first intended to register all of these aircraft in Bulgaria, as Liberian planes were then grounded due to United Nations restrictions. However, LZ-TPC was again re-registered in Equatorial Guinea as 3C-QQX. But due to licence difficulties, it had to remain parked at Ostend Airport for an unknown period of time. A further registration number, N822DE (*10), was then assigned in March 2002, and rumour has it that the aircraft was in a very advanced state of corrosion and would be dismantled for spares. [10]

In January 2002 Ducor World Airlines purchased the additional four TriStar aircraft from JMC Airlines/Caledonian Airways. One of them was re-registered as 3C-QRL, also in Equatorial Guinea, a tiny African republic, where most of Victor Bout’s fleet has been registered (see further on). The aircraft arrived early March at Maastricht, in the Netherlands, and was then ferried to Eindhoven initially to be operated as a flying exhibition for the Dutch Philips electronic products, but it became since 2003 again active with DWA from Sharjah. The third aircraft, re-registered as 3C-QRQ, was at first flying from Maastricht mainly to African destinations, has been involved in arms deliveries to Liberia (see below) and is since October 2003 Liberia-registered A8-AAA. The two other TriStar planes were, after Ducor went bankrupt in 2003, intended to become Liberia-registered too.

Belgian authorities were asked for more scrutiny to the Lockheed, stored at Ostend Airport. Indeed, the story of the aircraft N822DE (msn 1152) appears to be quite complicated [11]. Previously belonging to LTU Airways, it was since 1995 stored at Tucson, Arizona (USA), and its owner was Avtec AG. From May 2001 it was stored at Ostend Airport, belonged to Liberia World Airlines Gibraltar, and was first registered LZ-PTC, then re-registered LZ-TPC. In August 2001, LWA was renamed Ducor World Airlines and the aircraft got its Equatorial Guinea registration 3C-QQX. In March 2002, the Lockheed was eventually bought by Duane Andrew Egli, director of LWA/DWA and Westland Aviation and since 2001 an American citizen living in Miami, and the aircraft got its final American registration N822DE. [12] After a period of 18 months without executing a single flight, the Lockheed took off from Ostend Airport on 31 January 2003 bound for Canada, but the aircraft had to make an emergency landing at Manston Airport in southern England, after two of the three engines failed. In May 2003 the aircraft was ferried to an airport in Miami to be broken up. (*11)

Investigation by Bulgarian authorities showed that a company owned by a Bulgarian citizen, Yordan Zlatev, had applied for the Lockheed’s Bulgarian LZ-registrations. Zlatev is also a partner in Sitrat Air together with Volodya Nachev, who is a partner of Victor and Sergey Bout in the Bulgarian private air carrier, Air Zory. [13]

UN-investigation established that the Gibraltar company, KAS Engineering, through its branch in Sofia, KAS Engineering Teximp Bulgaria, acts as the sole broker of all the exports from Bulgaria-based arms suppliers. Victor Bout was the main transporter of these arms towards Africa’s war zones. He also provided the counterfeit end-user certificates to KAS Engineering. With regard to the settlement of the arms transactions, funds have been transferred to a Standard Chartered Bank account of the KAS Engineering branch in Sharjah (United Arab Emirates), the home of Victor Bout, before he fled to Moscow. [14]

All this makes LWA/DWA suspected of being closely linked to international arms dealer Victor Bout, who started his evil business in 1995 in Ostend. [13]

The involvement of DWA in arms traffic was again evidenced, when end March 2003 Charles Taylor provided the UN with a list of weapons that Liberia had procured for its self-defence from the Serbian arms manufacturer Zastava. The broker for the arms deal was Belgrade-based company Temex. Between May and the end of August 2002 an Ilyushin of Moldova’s Aerocom and the Lockheed 3C-QRQ of Belgium’s Ducor World illegally transported the weapons to Liberia. [15a, 15b]

After Ducor’s bankruptcy in July 2003, confirmed by Ostend’s station manager, Paul La Roche, both planes 3C-QRQ and 3C-QRL, have been sold to a new Liberian company, International Air Services, and Liberia-registered respectively as A8-AAA (*12) and A8-AAB. Also known as Air Express Liberia, the company was founded in 2003 and is the latest creation of Duane A. Egli. Both planes, so far still airworthy, are operated by the new Liberian airline on behalf of an also new and Dakar-based company, Georgian Cargo Airlines. The two remaining TriStars of bankrupt Ducor, purchased from Caledonian Airways and also intended to be registered in Liberia, have not been taken up because of their very poor condition. International Air Services itself seems to lease occasionally for single flights Ostend visiting aircraft from other airlines, such as Egyptian Air Memphis’ Boeing 707 SU-AVZ (*13), since 2 April 2004 derelict in Cairo, and DC8 planes of African International Airways of Swaziland, recently convicted of arms traffic towards the eastern Congo province of Ituri (see further on).

4. In December 1997 Air Charter Service (ACS) set up a new company at Ostend Airport. ACS had already offices in Moscow with Sergey Vekhov. [16] as managing director and in England where the nerve centre for Western Europe is installed under the leadership of a Briton, Christopher Denis Leach [17]. Chr. Leach started up the new company, Air Charter Service Belgium, together with a Dutch companion, Cornelis Schonk, who was until 1996 one of the members of the Board of Directors of Westland Aviation. The management of the new Ostend company was placed in the hands of Nicholas Leach. One of the aircraft operated by Air Charter Service Belgium from Ostend Airport, was an ageing Boeing 707, Liberian-registered as EL-ACP (*14), which, in accordance with European regulations, was allowed to take off until March 2000.

Once in an interview the British pilot Brian Martin let slip that he had in recent years regularly airlifted AK47 assault rifles to Central Africa as well as medical supplies for UNICEF. Brian Martin is known as the co-owner of Occidental Airlines (see further on). Alerted by this interview, a British pressure group started an investigation and identified the Boeing EL-ACP, being used by the Ostend company Air Charter Service Belgium for illicit arms transportation on the orders of a group of Dutch brokers.

Flight documents show that on November 3, 1999 the aircraft left Ostend empty for Burgas in Bulgaria. It took off at 14.56 hours as flight number ACH252F. After a fuel stop at Aswan, Egypt and having flown over Kenya under radio silence, it arrived the next day in the Zimbabwean capital Harare, carrying 40 tonnes of military equipment. According to Amnesty International, the airport commandant at Ostend said he had interviewed the Belgian flight engineer on the trip in question, who confirmed that the cargo included anti-tank shoulder-fired weapons. Military experts believe the cargo included a Bulgarian portable surface-to-air missile system. The 40 tonnes of equipment were transferred to an Ilyushin freighter and flown to Kinshasa.

For its very last flight from Ostend in March 2000, EL-ACP was again planning the delivery of weaponry to Harare, intended for the Zimbabwean troops supporting Laurent Kabila against rebel forces backed by Rwanda and Uganda. On March 15 at 13.52 hours the plane took off under flight number ACH007 for Bratislava in Slovakia, where it had to collect its items for delivery to Zimbabwe. [18]

On June 5, 2001, Air Charter Service Belgium went bankrupt, but ACS activities from Ostend Airport continued under the direct management of ACS chairman, Christopher Dennis Leach. In May 2005 ACS finally switched Ostend as its aircraft base for Nottingham’s East Midlands airport.

Two companies, mentioned below, which were actively involved in arms dealing, disappeared from Ostend in 1997/98. However, the owner of the first mentioned company is back in Belgium and recommencing covertly his prior activities. The two companies are:

▪ Occidental Airlines

▪ Trans Aviation Network Group

1. In August 1997 a newspaper report indicated that Occidental Airlines, a company based at Ostend Airport was under investigation by the public prosecutor of Bruges. [19] Until 1998 Occidental Aviation Services NV, as the company was officially registered at the Ostend Commercial Trade Register, had its own large warehouse next to the airport control tower. Although it was pretended that his wife was the owner of the company, a former Belgian airline pilot, Ronald Rossignol, was in fact the owner, together with the British pilot Brian Martin.

Ronald Rossignol is the son of a senior political appointee in the office of P. Van den Boeynants, at the time when the latter was serving as Belgium’s Minister of Defence. [20] Ronald Rossignol had, prior to 1980, close connections with Brussels extreme right wing circles. [19] Since 1980 he has been involved in business with the Congo’s erstwhile President Mobutu. According to the Belgian newspaper Le Soir, his name appeared on Interpol lists and he was arrested in 1984 in France and accused of fraudulent bankruptcy, to the extent of some BEF 800 million.

Despite the dubious past of R. Rossignol, placed once more under judicial scrutiny, a senior civil servant of the Flemish authorities, Paul Waterlot, responsible for Ostend Airport’s promotion and information, eagerly defended R. Rossignol publicly in the press and reaffirmed in the name of the airport’s management board, full confidence in the aims of, and the services provided by, Occidental Airlines. [21]

The subject of the judicial investigation was a cargo of nearly forty tonnes of military equipment, to be sent to governmental or rebel forces in Angola. An Avistar Airlines Boeing 707 freighter, Cyprus-registered as 5B-DAZ (*15), was chartered for the trip by Occidental Airlines. Pending a Belgian Customs investigation the consignment, consisting of Dutch Army surplus items, had been impounded in Occidental’s warehouse for nine months. The cargo manifest showed an innocuous cargo of used clothing, vehicle parts and vehicles, but the cargo consisted of twenty tonnes of uniforms, an armoured car, multi-band radios and other equipment needed by a fighting force. After being impounded for nine months, the consignment was granted permission to be exported to England and was merely sent across the Channel by truck without arousing further interest.

On 12 May 1998 the Avistar aircraft took off from the civil airport side of RAF Manston in Kent, UK bound for Africa. The flight plan showed that the aircraft was bound for Kano in Nigeria to refuel and then to its reported final destination of Mmabatho in South Africa. After taking off from Kano, the aircraft temporarily disappeared. It never landed on Mmabatho’s runway, actually too short for a fully-laden Boeing 707, but it was observed around 04.00 hours on 13 May on the ground at Cabinda, Angola and reappeared some hours later at Lomé in Togo, empty. [22]

According to the UK newspaper The Observer of 14 March 1999, the same aircraft 5B-DAZ, which in 1997 made some 28 flights from Ostend flew, in December 1998, a cargo of weapons and ammunition from Hermes, the former Slovak state-owned arms manufacturer in Bratislava, to the Sudan, in breach of an EU embargo. The southern civilian population of the Sudan is subjected to violent oppression on religious grounds. The money paid by Hermes for the flight was split between the pilot, the crew and Ronald Rossignol, who acted as broker. While on its way for another delivery to the Sudan and again chartered by Rossignol, the aircraft left Bratislava on 7 February 1999, failed to achieve sufficient speed and ploughed into the mud at the end of the runway. Because of its long list of ongoing malfunctions, it was decided not to repair the aircraft.

In January 1999, the London Sunday Times reported that Occidental Airlines, together with the London-based Sky Air Cargo, was using ageing Boeing planes to transport about 400 tons of military equipment, 40 tons at a time, from Bratislava to Sierra Leone, from where the equipment was flown to rebel Congo airstrips, especially Goma and Kisangani. [6]

A Romanian daily, Evenimentul Zilei, reported in March 2002, that besides the Sky Air’s plane EL-JNS as already noted, aircraft of a company cooperating with Victor Bout’s arms smuggling, Flying Dolphin, as well as the aircraft chartered by the Belgian trafficker Ronald Rossignol used the military section of Otopeni airport, near Bucharest, as a touchdown base before leaving Romania, loaded with arms from Romanian company, Romtehnica.

Ronald Rossignol succeeded in his efforts to remain outside the grip of Belgian justice, which probably had insufficient legal grounds to take him into custody. The incapacity of local justice illustrates clearly the need for comprehensive international legislation and law enforcement, as well as underlining the ease with which arms brokers are able to take advantage of gaps within and between national legal systems.

It is reported from several sources that Ronald Rossignol restarted since January 2001 his activities as manager of a company, called Red Rock and based at Brussels South Airport (see further on), while Belgian Justice again seems to skip the opportunity of some action.

2. Another Ostend-based company, which until 1997 was involved in arms smuggling, was NV Trans Aviation Network Group (hereafter “TAN Group”). The company was founded in 1995 and had its main office lodged in a brand-new building, called Jet Center, at the end of the motorway from Brussels to Ostend. The parent company of TAN Group, Air Cess is based in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, and seems to perform a pivotal function amongst different aircraft companies trafficking in arms. The brain of the organisation is a Russian ex-KGB major, Victor Anatolevic Bout (previously referred to), native of Tajikistan and undoubtedly on excellent terms with Russian and Ukrainian mafia and with former KGB-colleagues. As already noted, Victor Bout bought himself a luxurious house in a residential quarter of Ostend. His Belgian partner was a pilot, Ronald Desmet, formerly resident in France near the Swiss border.

Involvement in arms smuggling was first evidenced, when an insider revealed that Ronald Desmet paid the Air Cess-pilots USD10,000, in addition to their usual salaries, for each flight carrying arms and munitions. These flights were at that time mostly intended for Afghanistan. When this became known in Ostend and leaflets [23] with the names of those involved in illegal operations began appearing in mail boxes, Bout and his company Air Cess disappeared from Belgium, according to the director of IPIS and UN expert on illegal arms trade, Johan Peleman. [24] TAN Group decided in July 1997 to cancel the lease of its rented offices and to move to its Geneva office as well as to the parent company, Air Cess, afterwards renamed Air Bas, in Sharjah.

Ronald Desmet had formerly flown for the Saudi royal family [25] and held the authority to conduct business in the United Kingdom on behalf of the Liberian Aircraft Register. [26] Using these facts as proof of his integrity, he succeeded even in becoming a member of the Ostend Rotary club.

After he left Ostend, Victor Bout just went on with his sanctions-busting activities. According to a 1999 report of HRW, he had founded a subsidiary of Air Cess/Air Bas based at the South African airport of Pietersburg, called Air Pass. From Pietersburg, Air Pass, against UN regulations, transported fuel tanks, towing trucks, food and mining equipment to Unita-held areas of Angola. [27] During its activities, Air Pass had a direct link with a South African agency, Norse Air Charter, a subsidiary of the British air charter company Air Foyle of Luton. According to The Guardian (5 August 2000), it appears that Air Foyle had, through Norse Air Charter, a two-year business partnership with Victor Bout. [28]

Between July 1997 and October 1998, 37 flights left Burgas in Bulgaria carrying weapons worth $ 14 million and ending up in the hands of Unita forces in Angola, according to a UN-report of 21 December 2000. Victor Bout provided forged end-user certificates to the Gibraltar-based company KAS Engineering (previously referred to), which contracted the arms shipments from Bulgarian suppliers.

Shortly after South African authorities suspected him of smuggling arms to the Unita rebel forces, Victor Bout moved his operations to another company Air Cess Swaziland at Manzini airport. After the Swazi authorities discovered that his company was transporting military equipment, Victor Bout decided to move completely from southern Africa and to make Bangui in the Central African Republic his new African stronghold. [27]

On 19 April 2000 an Antonov aircraft AN-8, registered TL-ACM in the Central African Republic, crashed at an airport of the Democratic Republic of Congo, shortly after takeoff. There were no survivors. It was on a return flight with Rwandan army officers and some soldiers on board. The plane appeared to belong to Centrafrican Airlines, based at Bangui and to be co-owned by Ronald Desmet, the Belgian partner of Victor Bout. [14] Elsewhere an un-named company of Victor Bout has been reported flying in 1999 between the Central African Republic, Kisangani, the Congo and Kigali, Rwanda carrying arms, timber and precious stones. There is indeed also another company in Kigali, called Air Cess Rwanda, working with Russian and Ukrainian crew members and focussing its arms trade on the eastern region of the Congo and Angola. [29]

According to The Guardian, Victor Bout, who repeatedly changes the spelling of his name, is thought to operate a cargo fleet of some 20 ex-Soviet aircraft through several associated cargo companies based in various countries. It is almost impossible to trace all the aircraft linked with Victor Bout and his activities, since it is known that he usually leases his freighter aircraft to other operators and so can claim ignorance of the business of sanctions-busting. However, two of Air Foyle’s Antonov 124s made several flights to and from Ostend during the two-year partnership of the British company with Victor Bout. In January 1999, a plane belonging to Victor Bout was flown in conjunction with aircraft of Sky Air and the partly Belgian-owned Occidental Airlines, to airlift arms from Bratislava to war-torn but diamond rich Sierra Leone. [6] Four of Bout’s Ilyushin aircraft are registered in Equatorial Guinea, a tiny African republic located between Gabon and Cameroon. [30] Two of them were recorded in October 1999 at Ostend Airport’s official flight log, making flights to the United Arab Emirates. On a few occasions Victor Bout called upon the services of a company, known as Phoenix Aviation and owned by an Israeli of Russian origin. Two Phoenix Ilyushins were observed in August 1999 in Ostend and the last flight of one of them from Ostend was recorded in the official flight log on 29 January 2000 towards Khartoum in the Sudan.

According to the UN-report of December 2000, Victor Bout “oversees a complex network of over 50 planes, tens of airline companies, cargo charter companies and freight-forwarding companies, many of which are involved in shipping illicit cargo”. [31]

(Quick jump to Victor Bout’s air cargo companies!)

Challenged in 1997 to take legal action and to prevent the use of Belgian airports by Victor Bout’s companies and other companies suspected or convicted of arms trafficking, Belgian authorities retorted that such companies were not subject to the existing Belgian jurisdiction and thus admitted that this legal inadequacy indeed enables abusers to take advantage of the gaps within and between the different national legal systems. The result of the investigation, ultimately ordered by the Ministry of External Affairs, has never been published.

After Victor Bout swapped his action field in southern Africa for a safer one in central Africa, he was actively assisted by Sanjivan Ruprah, a politically well-connected Kenyan businessman of Indian extraction. Ruprah introduced Victor Bout in arms dealings with Liberia’s president Charles Taylor and with rebels in eastern Congo as well as in Sierra Leone. After his relationship with Charles Taylor started to deteriorate, Ruprah moved to Belgium in mid-2001 and was arrested in Brussels on 5 February 2002.

Victor Bout did better. Until allegations in the US media surfaced about links with Al Qaeda, Bout operated with impunity in Western democracies, former Eastern Bloc nations, and the developing world, through a maze of companies, exploiting lax and outdated regulations and changing his aircraft registrations from one country to another. Although for a long time the US authorities had turned a blind eye to his activities, Victor Bout suddenly became a main target of the US and the Western alliance, after the 11 September catastrophe and the subsequent assumption of his purported connections with Al Qaeda, until now not supported by any conclusive evidence.

Victor Bout had then to take refuge in Moscow, where he adamantly declared in the studios of radio Ekho Moskvy: ‘I deal exclusively with air transportation.’

However, Victor Bout’s alleged previous link with Al Qaeda doesn’t mean, in the view of US officials, that the US and UK governments shouldn’t cooperate with him. Indeed the US-UK coalition forces are using airlines owned by Victor Bout to transport supplies to Iraq. In 2003 a subsidiary of the British Gulf International Airlines (BGIA), headquartered in Sao Tome & Principe and with base in Sharjah, was created in Kyrgyzstan, and uses name, offices and staff of its Sao Tome counterpart. Intelligence agencies have linked Bout to this firm’s planes, and money transfers have been traced between BGIA and a Bout-linked company, San Air General Trading. BGIA’s flight manager admitted that his firm frequently flew supplies to several Iraqi locations. Also Bout’s Kazakhstan air company, Irbis Air, which took over assets and operations from Bout’s Air Cess/Air Bas, frequently flew into Iraq. Irbis planes bought fuel 142 times from military stocks in Baghdad. [32] Since Iraq airports are now the world's most dangerous, Bout's aircraft, pilots and personnel provide the US authorities with "plausible deniability" in case an airplane is downed. It is believed that Bout will be amnestied from the multitude of international charges he faces in return for his services. Indeed, in 2004 the Bush administration began to press for Bout to be left off planned UN sanctions, in spite of French efforts to freeze his assets and an outstanding Interpol warrant for his arrest. [33] When Condoleezza Rice was National Security Adviser, she pre-empted an attempt by United Arab Emirates authorities to arrest Bout at Sharjah and gave clear orders to the CIA and FBI not to touch him. [34] Through BGIA and Irbis Air, Bout is now running arms for the Bush administration.

To whatever degree Ostend Airport has hosted major arms dealers, the airport continues being the host to some dubious companies. There are additional disturbing facts to be anxious about, including the precise role of Ostend Airport in what has been described as “the octopus that is the arms trade”. Additional disturbing facts are:

▪ According to the UK’s Daily Express of 9 June 1996, in April 1996 the British pilot Christopher Barrett-Jolley bought a small BAC 1-11 freighter that was due to be scrapped, and persuaded the British authorities to allow him to fly it to Ostend, supposedly to sell the parts. Once there, however, he put the plane on the Liberian register and formed a new company, Balkh Air, to fly arms from Bulgaria to a warlord in northern Afghanistan. Barrett-Jolley was also the pilot, who should have flown the arms-laden Boeing 707, 5B-DAZ, chartered by Ronald Rossignol’s Occidental Airlines, from Bratislava to Khartoum in the Sudan on 7 February 1999. Ironically, he could then not be present to fly the plane. So an unlicensed crew boarded the freighter, but unaware of its defects they failed to get the plane into the air and, as recounted earlier, it crashed into the mud at the runway’s end. Another old Boeing 707 with Afghan registration YA-GAF (*16a) has been standing since 1997 on Ostend Airport in a state of increasing dilapidation and was ultimately broken up end of June 2004 (*16b). First owned by Uganda Airlines, it was afterwards owned by Balkh Air, the company of the enigmatic British pilot and moreover linked to one of the most cruel warlords in Afghanistan, Rashid Dostum.

Barrett-Jolley’s unlawful behaviour is further illustrated by his due appearance in court on 19 October 2001. A few days earlier, after a Boeing 707 freighter (msn 19179), registered in Equatorial Guinea as 3C-GIG (*17), arrived at night from Jamaica at Southend Airport, Essex, UK, pilot Barrett-Jolley was caught red-handed and charged with smuggling 270 kilos of cocaine with an estimated street value of £22 million. [35] The plane had been chartered by Ronald Rossignol’s new Belgian company Red Rock, based at Brussels South Airport and which he manages since its establishment in 2001. The plane, now registered as 9L-LDU (*18), was sold in October 2003 to and is still active with Air Leone, formerly Ibis Air Transport and controlled by Executive Outcomes and its sister company Sandline International. [36]

In 1994 Barrett-Jolley flew arms to the Unita rebels in Angola and to South Yemen during the vicious civil war. In December 1994, one of his planes crashed outside Coventry airport, due to outdated equipment and improper maintenance, killing five people.

▪ In 1997 an ageing Boeing 707, registered as 5Y-SIM (*19), made 39 flights from Ostend Airport. The aircraft was operated by the Kenyan company, Simba Airlines, formed by Sanjivan Ruprah, a close associate of notorious arms dealer Victor Bout. Due to European Community directives, Simba Airlines lost in 1998 its landing allowance on Belgian airports. Sanjivan Ruprah, himself an arms broker, was also linked to the private military company (PMC), Executive Outcomes, responsible for killing many African people during the civil wars in Angola and Sierra Leone. He was in charge of Simba Airlines, until investigations into financial irregularities forced the company’s closure. [37] There was also a close company relationship between Simba Airlines and Ibis Air Transport, that became in 1999 Executive Outcomes’ airline company Air Leone, based in Freetown, Sierra Leone. Sanjivan Ruprah was arrested in Belgium, after evidence emerged of links between Victor Bout and the Taliban regime in Afghanistan.

▪ In May 1997 a Boeing 707 of Ibis Air Transport, alias Air Leone, alias Capricorn Flights, and registered as P4-JCC (*20) visited twice Ostend Airport. It was also seen at Sharjah in February 1998. Before that, it had visited Ostend registered as YR-JCC and operated by the Romania-based company, Jaro International. The aircraft was later sold to the Sudan-based Azza Transport Company.

▪ Before Victor Bout started his business in Ostend, the airport of this town was, according to Human Rights Watch, already since at least 1994 harbouring aircraft connected with arms deliveries to embargoed African countries. In its report on the April 1994 Rwandan genocide [38], HRW reported that an arms shipment arrived in mid-June 1994 in Goma on an aircraft registered in Liberia, with a Belgian crew from Ostend, which picked up arms in Libya, including artillery, ammunition and riffles from old government stocks. This arms shipment was probably the one to which the leaflets [22] distributed in Ostend mail boxes alluded, bringing this Liberian-registered aircraft into connection with Bout’s associate, Ronald Desmet, who had boasted in the presence of a local Ostend politician, that he held the authority to conduct business on behalf of the Liberian Aircraft Register. [25] However, these weapons were then to be delivered from Goma in what was then known as Zaire to the Rwandan Hutu armed forces at Gisenyi, just across the Rwandan border.

An earlier flight with arms took place on 25 May. A Boeing 707 aircraft, Nigerian-registered as 5N-OCL (*21), arrived at Goma carrying 39 tons of arms and ammunition. [39] The aircraft was said to have carried a single passenger, listed as “Bagosera T.”. It is also known that Colonel Théoneste Bagosora, a top official from the former Rwandan government forces and reputed to be one of the main organizers of the April 1994 genocide, was at that time eagerly in search of weapons to counter the Tutsi RPF armed forces. [38] The 5N-OCL Boeing was operated by Overnight Cargo Nigeria, a short-lived company from 1992 to 1994, period in which the Boeing was a regular visitor to Ostend Airport.

▪ In its Bulgaria report of 1999, HRW mentions the case of a Boeing 707 flying from Burgas to Bujumbura, Burundi, and grounded in Lagos, Nigeria, after weapons were discovered on board. The plane was operated by Trans Arabian Air Transport of Sudan, left Burgas airport in mid-February 1998, and made a stopover in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, where part of its cargo was unloaded, before stopping in Lagos to refuel on its way to Burundi. A close aide to Burundian president Buyoya was aboard the plane and was later promoted to the post of defence minister. [40] Two of the Trans Arabian Air Transport Boeings, 5X-ARJ/ST-ANP (*22) and ST-AMF (*23), made in 1997 a combined total of 45 flights from Ostend Airport.

▪ On 17 November 2000, a 33 years old Boeing 707, owned by Equaflight Service, an airline company with operating base at Pointe Noire, Congo-Brazzaville, landed at Ostend Airport. It was registered as TN-AGO (*24). Before that, it was operated by Air Ghana and registered as 9G-AYO. Just before becoming TN-AGO, the plane was temporarily Thai-registered as HS-TFS, astonishingly the same registration number which was seen on another aircraft in September 1999 (see further on). The previous ‘Thai Flying Services’ titles were still slightly visible on this new-registered aircraft. However, in 1997 the same aircraft, registered as EL-RDS, made 6 of the 12 flights executed in that year from Ostend Airport by airplanes of Air Cess, one of Victor Bout’s main airline companies. Four of the 12 flights were executed by the Air Cess Ilyushin EL-RDX, which became afterwards registered as TL-ACU and operated by Bout’s Centrafrican Airlines and whose deliveries of helicopters, other military equipment and ammunition in July and August 2000 to Liberia are well documented. [41] On 4 January 2001, TN-AGO took off from Ostend for Chateauroux in France. On 7 September 2001, the airplane crashed at Lubumbashi in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and sustained substantial damage when the undercarriage collapsed and two engines detached.

▪ Another aircraft seen at Ostend Airport, has been involved in illegal arms traffic. On 29 September 2001 an Antonov-12, registered as UR-UCK and owned by Ukrainian Cargo Airways, landed at the Bratislava airport. The aircraft was expected to pick up for onward shipment to Angola additional cargo, that just before had been unloaded from an Iranian Ilyushin plane. This Iranian cargo appeared to be 504 units of rocket-propelled grenades, but it did not match the consignment-note. Consequently the munitions cargo was impounded and so prevented from being loaded onto the Antonov-12, which was allowed to take off for a military airport in Israel en route to Angola, after Slovak authorities had been pressurized to release the consignment. UR-UCK’s own cargo, collected on departure from Ukraine on behalf of the Israeli private military company LR Avionics Technologies, consisted of spare parts for military aircraft. During a fuel-stop at Mwanza in Tanzania [42], the aircraft was halted, since authorities discovered undeclared weapons cargo. Nevertheless, it was allowed to leave on orders of top Tanzanian security officials.[43] LR Avionics is known to belong to former military pilots and to have sold under controversial circumstances Ukrainian radar systems for military and civil use in Angola, Congo and Ethiopia. [44]

The aircraft UR-UCK also visited Ostend from 2000 to 2002 and was in the second half of 2002 leased in by the Ostend-based company Air Charter Service (*25).

As recounted earlier, Moldovan Aerocom was, together with Belgium’s Ducor World Airlines, convicted of illegal arms transport to Liberia in the summer of 2002 [15b]. After its gunrunning was the subject of too much public exposure, Aerocom got its airtransport operating certificate revoked in August 2004. Asterias Commercial, a company in Greece with base in Ukraine, but since its creation in 1996 left as a dormant shell company, was promptly reactivated so as to continue Aerocom’s operations.

One of Asterias’ airplanes was frequently seen at Ostend, since it was leased from november 2004 to Ostend-based Air Charter Service. (*26)

▪ On 31 December 2002 an airplane, registered in the Central African Republic (CAR) as TL-ADJ (*27), requested to make an emergency landing at Ostend Airport, since the landing gears didn’t come in after take-off in Southend. In 1997 this plane, registered as 9Q-CBW (*28), was a regular visitor to Ostend Airport and executed 106 flights from Ostend on behalf of Scibe Airlift Congo. This company closed down and the plane was then stored at Southend airport. After 5 years of storage, the plane was supposed to leave on 13 December 2002 for Tripoli, Libya, but due to technical problems the aircraft was kept on the ground. It left then Southend on 31 December bound for Mitiga, Libya, but within 30 minutes it landed at Ostend. On 3 January 2003 the aircraft was supposed to leave Ostend for Mitiga, but again it was kept on the ground. Technical control, ordered by the Belgian authorities, showed a long list of deficiencies. The logo on the plane’s tail ‘AL’ stands for African Lines, a company which is probably linked to Centrafrican Airlines of the Belgian pilot Ronald Desmet, former associate of notorious arms dealer Victor Bout. According to UN-reports, Centrafrican Airlines is known for having airlifted arms from Bangui in the CAR to several war zones in Africa, mainly those in the DRC. According to the Belgian daily De Morgen of 24 January 2003, it also appeared that Jean-Pierre Bemba, the leader of the rebel movement MLC (Mouvement de Libération du Congo) was immediately lobbying to get the aircraft in the air and it was known that Bemba, still fighting then for primacy in the northern part of the DRC, got arms and ammunition airlifted from the CAR. Eventually under ongoing pressure of Bemba, who meanwhile became one of the six vice-presidents of the transitional government of the DRC, and after a French company willingly delivered a valid “release to service” certificate, the aircraft took off from Ostend on 6 August 2003 and minutes later ended up at the airport of Reims in France, after again an emergency landing.

The defunct airline company Scibe Airlift was owned by Jean-Pierre Bemba’s father Bemba Saolana, a wealthy businessman in the then Zaire under Mobutu. The company kept offices at Ostend Airport, called Scibe CMMJ. Bemba Saolana and one of Mobutu’s sons controlled in addition to Scibe, several smaller airline companies, that formed the vital lifeline that enabled Unita to re-emerge as a highly capable rebel movement in Angola in the mid 1990s. Scibe Airlift had one of its planes grounded when it refused a customs check after arriving at N’Djili airport in Kinshasa from Belgium in early 1997. [45]

▪ An ageing Ghana-registered Boeing 707 (9G-EBK) made about ten flights with arms from Plovdiv in Bulgaria to South Yemen. This was at a time when that country was subject to an international arms embargo. The aircraft was operated by the Ghana-based company, Imperial Cargo Airlines, and was seen with this registration at Ostend Airport. In 1997 the same aircraft, registered as 9G-SGF, made 40 flights from Ostend Airport and was then operated by the Nigerian-based Sky Power Express Airways and leased from Ghana’s Al-Waha Aviation, owner of this sole airplane. With the Thai registration number HS-TFS (*29), already seen before on another plane, as pointed out earlier, the aircraft reappeared at Ostend Airport in September 1999 with titles of the operating company, Thai Flying Services. It took off from Ostend for Sharjah, which reportedly became its new home base. Afterwards the plane with a new registration (9G-JET) was sold to Johnsons Air of Ghana, which has Accra and Sharjah as operating bases and is closely associated with a Belgian company First International Airlines.

▪ On 18 November 2000, the day after the Equaflight Boeing TN-AGO landed in Ostend, a 35 years old Boeing 707 (9G-LAD) owned by Ghana’s Johnsons Air, landed at Ostend Airport. In 1997 this plane was operated by a Nigerian company, Merchant Express Aviation, based in Lagos, and registered as 5N-MXX (*30), it made 83 flights from Ostend Airport. In 1998 Merchant Express ceased all activities and the aircraft became Johnsons Air 9G-LAD (*31). Johnsons Air works in league with the Belgian company, First International Airlines. The company, first based near the town of Tournai, is now based in Brussels. It has office and PO box at the Ostend Airport and uses the air transport operating certificate of Ghana’s Johnsons Air. The man in charge of First International is an Iranian, Niknafs Javad. He was a pilot who, earlier in his career, flew for David Tokoph’s Seagreen. It is not clear if his company still works as a subcontractor for Tokoph. Rumours that First International Airlines is flying arms between Azerbaijan and China have not been confirmed. Another Johnsons Air Boeing 707 (P4-OOO) operated by First International and seen at Ostend Airport, crashed on 16 January 1997 on Kananga airport in the former Zaire. As the right main gear collapsed on landing, the aircraft ran off the side of the runway and caught fire.

First International is also related to an obscure airline company, Cargo Plus Aviation, registered in Equatorial Guinea and with bases in Dubai and Sharjah. The First International office at the airport bears the nameplate with corresponding logo of Cargo Plus, and both companies share their commodities. Meanwhile they left their office at the airport for another office in town.

▪ At Ostend Airport, Johnsons Air itself shares since the end of 2003 office, station manager and PO box with HeavyLift, which is part of Christopher Foyle’s airline company Air Foyle, as recounted earlier, known from its two-year business partnership with arms dealer Victor Bout. [27] HeavyLift seems to be the air broker, who organises from Ostend the Johnsons Air flights. However, both companies recently left the Ostend airport after a few adverse publications.

Johnsons Air was formed in 1995 by Farhad Azima, a native of Iran, resident in the U.S. since the 1950s and member of the Board of Directors of the U.S. Azerbajan Chamber of Commerce [46]. At the time of HeavyLift’s shutdown, Azima was its chairman. Reputed as a mayor gunrunner [47], he is also suspected to have had close ties to the CIA and has been linked to the Iran-Contra arms-for-hostages scandal as well as to all kinds of criminal activities [48].

On 7 August 2003 an ageing Boeing 707 landed at Robertsfield International Airport in war-torn Liberia. It was filled with arms including rocket launchers, automatic weapons and ammunition. [49] The Boeing was owned by Johnsons Air. It was bearing the same registration number as the just above described aircraft, 9G-LAD and was probably operating from Sharjah. In fact it was executing this flight in a series of three Johnsons arms flights to Monrovia. [50] But it is not quite clear which airline company was operating the plane at the time when it landed in Liberia. According to certain sources, the operating company might as well have been First International (*32) or Race Cargo (*33).